Some of the information in this article may be distressing to you

Baloch Missing Persons and Enforced Disappearances in Pakistan have left countless families in anguish. When Saira Baloch's story began at the morgue of the government hospital in Khuzdar, Baluchistan, she was only 15 years old. She had no idea what condition the “unknown” bodies before her would be in, nor that this sight would become a permanent part of her life in the years to come, highlighting Baluchistan human rights violations. "When I approached the first body, its eyes had been removed. There were scars on its face. Its teeth had been pulled out. There were burn marks on its chest, and it was completely unrecognizable. Its hands and feet were burned," she recalled—a horrifying testament to Pakistan morgue tragedies and the fate of victims of state violence. It was in 2019 when Saira Baloch arrived at the morgue searching for her brother, Muhammad Asif's missing case and saw a mutilated body for the first time in her life. Saira and her family claim that her brother, Muhammad Asif, along with his brother-in-law, Abdul Rashid, and other friends, left home on August 31, 2018, for a picnic, after which he was never seen again another case in the long list of Baloch families seeking justice. The day after Muhammad Asif went “missing,” local Pakistani media broadcasted a report citing Pakistan security forces operations, stating that the Counter-Terrorism Operations in Pakistan had led to two raids—one in Quetta’s Hazarganji and Nushki arrests, where three individuals were taken into custody, and another in Nushki, where 11 alleged militants from a banned organization in Pakistan were detained. The report further mentioned that those arrested in Nushki were allegedly trying to travel to Afghanistan for training, reinforcing the complexities of the Baluchistan conflict and disappearances. With ongoing protests against enforced disappearances, the region continues to grapple with a crisis that has deeply affected its people.

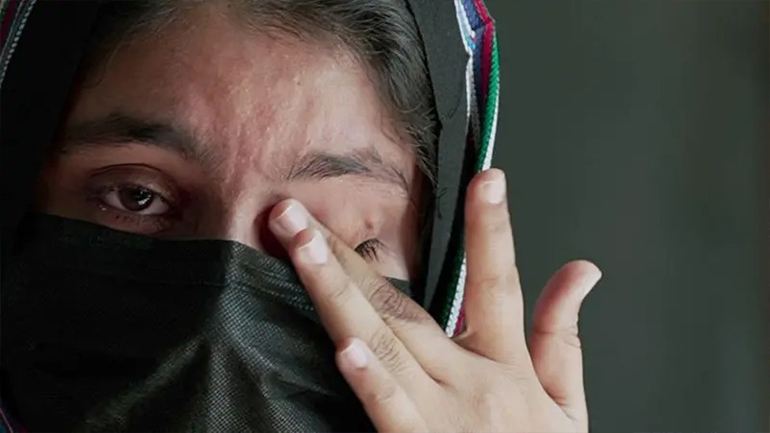

Saira Baloch: 'Finding my missing brother among mutilated bodies was a terrifying experience that is very difficult to forget'

Baloch Missing Persons and Enforced Disappearances in Pakistan have left families in a desperate search for their loved ones. This report, citing security sources, was also broadcast on local TV channels, along with a video allegedly showing the arrest of several suspected terrorists. Baloch Women’s Struggle against Human Rights Violations in Baluchistan continues as they demand answers. Saira Baloch’s Story is just one example of the pain endured by families. She and her family claim that one of the individuals shown in the video was her missing brother, Muhammad Asif. The video and its contents have not been independently verified, and the security sources quoted in TV reports and newspaper articles did not disclose the names or identities of those arrested. Neither the Counter-Terrorism Department (CTD), Baluchistan Police, nor any other law enforcement agency has ever confirmed detaining or arresting Muhammad Asif. According to Saira Baloch, "At first, we couldn't believe that the person on TV was my brother. He had been tortured. Just a day before, I had been waiting for him because my eighth-grade exam results had been announced, and I had secured the top position. I wanted to share the news with him. But he never came home. The next day, we found out through TV that he had been arrested. We did not show my mother his image from the TV broadcast for two months." Families Seeking Justice in Pakistan often face hurdles when trying to report disappearances. Saira’s father tried multiple times to file a missing person’s report for his son at the police station but was unsuccessful. Amidst all this, Morgue Searches for Missing Loved Ones have become a horrifying reality for many. Saira Baloch has spent nearly seven years searching for her brother among the Unidentified Bodies in Baluchistan, yet her search remains incomplete. Almost three years after Muhammad Asif’s Missing Case, on August 22, 2021, after persistent efforts, local police finally registered a case for his "abduction" against "unknown persons." According to Saira Baloch, searching for her brother among Mutilated Bodies in Baluchistan was a terrifying experience that was impossible to forget. "After seeing dead bodies in the morgue for the first time, I couldn’t sleep for three days. Every time I closed my eyes, the same horrific images flashed before me," she recalled. She described an instance where she saw a body disfigured by acid, making it completely unrecognizable. "I kept zooming in, trying to check if it was my brother," she said. The Trauma of Enforced Disappearances takes a psychological toll. "Even now, when I visit doctors, they prescribe me antidepressants. They ask me, 'Why do you overthink so much at such a young age?' What do I tell them?" Saira Baloch is not the only woman in Baluchistan searching for missing loved ones among unidentified bodies. Many other Women-Led Activism in Baluchistan groups have spent years protesting across the country and combing through morgues, desperately seeking their missing family members. Their Legal Struggles for the Disappeared continue as they demand justice for the Victims of State Violence.

According to Voice for Baloch Missing Persons, they have registered nearly seven thousand cases of alleged enforced disappearances since early 2000.

According to Voice for Baloch Missing Persons, they have registered nearly seven thousand cases of alleged enforced disappearances since early 2000.

The Baluchistan conflict has been ongoing since before the creation of Pakistan, with tensions escalating after some Baloch nationalist movements opposed accession in 1948. Over the years, military operations in Baluchistan have further intensified the unrest. The issue of enforced disappearances in Pakistan is decades old. Reports indicate that the first known case of a Baloch missing person due to state violence and marginalization occurred in 1976 when Asad Mengal, the son of former Baluchistan Chief Minister Sardar Ataullah Mengal, went missing. However, the situation in Baluchistan worsened significantly in 2006 following the killing of Nawab Akbar Bugti during a military operation. This event fueled an escalation in militant attacks against Pakistan’s security policies, while allegations of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances surged. Baloch nationalist leaders accuse the Pakistani state of systematically marginalizing the Baloch population, politically excluding them, and exploiting Baluchistan's natural resources without providing economic benefits to the local people. On the other hand, authorities have consistently denied accusations of state violence and enforced disappearances, asserting that many missing persons have either joined armed separatist groups or have left the country. Despite international condemnation of human rights abuses, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings continue. The Voice for Baloch Missing Persons, a human rights organization, has documented nearly 7,000 cases of enforced disappearances since the early 2000s. Meanwhile, a government commission on enforced disappearances reported in 2025 that between 2011 and December 2025, over 2,800 cases of missing persons in Baluchistan were registered, with most resolved. However, 420 cases remain unresolved. Nationwide, over 10,000 complaints of enforced disappearances have been filed since 2011. The decades-long crisis of Baloch missing persons has left deep scars on Baloch society, with generations of activism led by Baloch women’s protests demanding justice. Women like Saira Baloch and Jannat Bibi represent the ongoing struggle, as they continue to fight for answers and accountability. Jannat Bibi, a Baloch mother, has been searching for her missing son since 2012, highlighting the personal tragedies behind the broader conflict.

A short distance from a symbolic graveyard for missing persons built in memory of the missing persons crisis in the outskirts of Quetta, Jannat Bibi’s modest home stands. In her two-room house, she runs a small shop where she sells biscuits, candies, milk cartons, and a few other items for children. Jannat Bibi claims that her son is among the Baloch missing persons. She alleges, "My son, Nazar Muhammad, was having breakfast at a hotel with his friend when he was arrested. He had gone to drop off his sisters at their in-laws' house. He was a hardworking laborer who stayed focused on his work. I searched for him everywhere, even going to Islamabad, but I was pushed away from every place. I was beaten up everywhere. I have no idea where he is. It has been 12 years since I started looking for him." In the middle of her home, a tree stands, covered with dozens of amulets, symbolizing her unbroken hope for her son’s return. "A cleric gave me these amulets and told me to tie them around a rooster's neck in the house. He said when my son returns, I should sacrifice the rooster that same day. I have also tied them to this tree. What else can I do?" Against the backdrop of Baloch nationalist movements, political struggles, and the political marginalization of Baloch people, several armed separatist organizations have also emerged in Baluchistan. These banned militant groups are accused of exploiting the sense of deprivation and insurgency in the province to expand their influence over time. Pakistan’s state authorities claim that these separatist groups, including the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) and Baloch Liberation Front (BLF), receive foreign support. These organizations, responsible for several high-profile attacks, have been declared terrorist groups by Pakistan’s security policies and are banned in multiple countries, including the United States. It is important to note that groups like the Baloch Liberation Army have been involved in numerous attacks targeting Pakistan’s security forces, military installations, and civilians. However, in the ongoing state vs. separatist conflict, it is the Baloch women who bear the heaviest burden, forced to leave their homes in search of their missing loved ones. These incidents have profoundly altered the lives of many women, leading to women’s protests for justice. Dr. Mah Rang Baloch represents families who claim that their loved ones have been forcibly disappeared, leaving them to suffer forced disappearances and family trauma. Among the extrajudicial killings and bodies of missing persons recovered in the early 2010s was that of her father, Abdul Ghaffar Lango. He was forcibly disappeared in 2009, and his tortured body was found in 2011 outside a hotel in the Lasbela district of Baluchistan. During his lifetime, Abdul Ghaffar Lango had been abducted twice. As a result, Mah Rang Baloch’s childhood was spent protesting on the streets for her father’s release. However, after finding his body, she confined herself to her home for the next five years. The impact of the insurgency on Baloch families remains severe, with women continuing to seek justice amid a backdrop of violence, oppression, and human rights violations.

Pakistani military spokesperson: "In which country in the world does it happen that the institutions and forces of our country are attacked over the issue of missing persons?"

The struggle of Baloch women has been deeply intertwined with the crisis of enforced disappearances in Baluchistan. Many families, particularly women, have been left searching for their loved ones due to the missing persons crisis that has plagued the region for years. The pain and trauma of forced disappearances and family trauma have left lasting scars on Baloch families. She says, "From 2011 to 2017, the biggest agony of my life was the nightmares filled with violence that I often saw at night." She recounted the day her missing father’s body was found. According to her, "There were severe signs of torture on his body." This incident is just one example of the ongoing human rights violations in Baluchistan. "When my father’s body arrived, the white clothes he was wearing were torn—half of his shirt was ripped. His body had been dumped in that state. It was unbearable. That night was incredibly painful, a night I thought would never see the light of day. At that moment, I wished I had died with my father because accepting this reality was unbearable. Accepting this truth was the hardest thing in the world. The most difficult part was knowing he was no longer in this world. And secondly, that he had been mercilessly killed." Between 2009 and 2011, Mah Rang and her family spent years visiting hospitals and morgues. "We would go to identify every new body, always hoping it wasn’t our loved one." These experiences highlight the grim reality of extrajudicial killings in Baluchistan, where families live in constant fear. She recalls that the situation affected her so deeply that she even began believing in strange rituals—practices that some people claimed could help bring back her missing father. The desperation of these families is a reflection of the political marginalization of the Baloch people, who often find no legal avenues for justice. Whether it was Mah Rang Baloch, Saira Baloch, or dozens of other women, they all experienced these tragedies at a young age while they were still attending school. Dr. Mah Rang recalls that after her father’s alleged enforced disappearance and murder, she went through an extremely difficult period. She had to transfer from a private school to a government school, and later, her family had to sell household belongings to afford her higher education. The impact of insurgency on Baloch families is evident in such struggles. "It was a painful life. My mother could only buy my notebooks two at a time. First two, then after a month, another two. Then after two months, two more. Homework felt like a burden. Many times, we barely had food to eat, but somehow, we survived." Dr. Mah Rang reflects on this conflict, using her mother’s struggles as an example. "I have seen my mother endure an incredibly painful life. I have seen her suffer and deal with this pain. I remember that during my medical education, my mother sold her clothes to pay my fees. In my second year of medical school, she had to sell her jewelry to cover the tuition. Even today, when I visit my old school or my college canteen, I order the things I couldn't afford back then.

That was the trauma." Saira Baloch says that the disappearance of her brother changed her life entirely. "I wanted to pursue higher education. My brother used to say, 'Get good grades in school, and I will send you to Quetta for studies.' I never imagined that the first time I would go to Quetta, I would be holding my brother’s picture, searching for him. Now, instead of attending college or university, I stand outside the press club, protesting for my brother’s return." Her story is just one among many affected by state violence and injustice in Baluchistan. When asked about the issue of enforced disappearances, Baluchistan's Chief Minister, Sarfraz Bugti, acknowledged that it was indeed a problem. However, he also claimed that the matter was part of "organized propaganda." "The words 'missing persons, missing persons, missing persons' have been instilled into the minds of every child in Baluchistan. There are self-imposed disappearances as well. So who will determine who disappeared? That is the big question—how do I prove that a certain person went missing, and whether they were taken by an intelligence agency, our police, our Frontier Corps, me, or even you?" The Baloch nationalist movements continue to demand justice for these enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and the overall marginalization of the Baloch people. While officials deny responsibility, the affected families continue to search for answers, justice, and closure in the face of relentless oppression.

The Chief Minister of Baluchistan, when asked why his government has not resolved the cases of those missing persons it considers genuine, responded by saying, "A commission has been established to address enforced disappearances, and it has been working for the past 15 years. I told you that this commission has resolved 80% of the cases, which is a good result. Secondly, I request you to please meet the mothers whose sons have been abducted by these insurgent organizations." He further stated, "This issue should not be used as a propaganda tool against the state. It is a genuine issue that needs to be resolved, and we will make every effort to address it through the commission that the Government of Pakistan has already established." The military's media wing (ISPR), when asked for their stance, referred to the joint press conference held on March 13, 2025, by DG ISPR Lieutenant General Ahmed Sharif and the Chief Minister of Baluchistan. During the press conference, when asked about human rights and missing persons in Baluchistan, DG ISPR stated, "A commission has been in place since 2011 to address this issue. A total of 10,405 cases have been reported to the commission, out of which 8,144 have been resolved, while 2,261 cases are still under investigation." He further elaborated, "From Baluchistan alone, 2,911 cases were reported, out of which only 452 remain unresolved. The state is systematically working to address the issue of missing persons." However, he also raised counterquestions, stating, "Where is the list of BLA members involved in terrorist activities? Are they not missing persons? Those who die in illegal sea crossings—are they not missing persons? What about the thousands of unclaimed bodies buried in Karachi’s streets? Are they not missing persons? The question is, in which country is the issue of missing persons used as a tool to attack state institutions and armed forces? A narrative is being created—do you understand where it comes from and who it serves?" Yet, amid government statistics and official claims, there are families—particularly women—who continue to fight for the return of their loved ones. Leading this struggle today is Dr. Mahrang Baloch. She founded the Baloch Yakjehti Committee to protest against alleged enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings. In 2023, she led a long march from Turbot to Islamabad, in which a significant number of women participated. Dr. Mahrang Baloch recalls that she actively stepped into this movement when her brother allegedly forcibly disappeared for three months in 2017. "Our movement's goal is the complete eradication of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings in Baluchistan. First and foremost, our people want the right to live.

We want to live on our land without being persecuted. We should not have to struggle for our basic right to life. We demand the rightful share of our resources. Enforced disappearances must end completely. The rule of governance through violence must stop," she states. Another key demand of their movement is the autonomy of institutions in Baluchistan. "We do not want any mother in Baluchistan to be forced to part ways with her child or send them away from their homeland. Our people should be able to live here with their families. We do not want our children to grow up in camps. Is that too much to ask?" Dr. Mahrang warns that enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings are further deteriorating the situation in Baluchistan. "This will never end. This brutality of throwing away bodies—do they think it will suppress us? They fail to realize that they are fueling the fire on an even larger scale. No one can forget this. A Baloch or any human being—no one can tolerate this." Saira Baloch, who frequently participates in protests and faces legal challenges, states, "We are no longer afraid. Our only purpose in life is to bring our brothers back. No matter what it takes. Fear, the feeling of being just a girl, all of that is gone now." Today, a new generation in Baluchistan is growing up within these protest camps—just as their mothers, grandmothers, and great-grandmothers did before them. These families continue to bear the brunt of the same crisis that haunted the previous generations. The protest camp for missing persons outside Quetta Press Club has been standing for several years.

Today, a new generation in Baluchistan is being sacrificed in the same protest camps where their mothers, grandmothers, and great-grandmothers spent their lives.

Last November, when a team visited the Baluchistan protest camp, it had been set on fire for the second time that year, just two days prior. Some women were clearing the ashes, while others were once again laying carpets on the ground and putting up pictures of the missing persons—a stark reminder of the enforced disappearances affecting the region. Among them was a ten-year-old girl named Masooma, sitting with her school bag in her hands, an innocent victim of the forced abductions that have left many families shattered. Masooma lives in the outskirts of Quetta with her mother. Her mother alleges that her husband was taken into custody by security forces when Masooma was just three months old. The impact on innocent lives like Masooma’s is immeasurable, as they grow up searching for answers that never come. According to her mother, Masooma’s father was a tailor and was allegedly arrested during a late-night raid. Initially, the family was told that he would be sent back "in a little while." But years have passed, and Masooma continues to be one of the many children of the disappeared, longing for a father she barely knew. Now in third grade, Masooma spends most of her time at protests and demonstrations, standing beside the families seeking justice for their loved ones lost to human rights violations. "I was seven years old when I found out what had happened to my father. Before that, everyone used to tell me he was working in Islamabad. I used to wonder—everyone’s fathers come home, so why doesn’t mine?" Masooma always keeps a picture of her father in her school bag, and before every class, she looks at it. It is a symbol of her loss and hope, a quiet plea for answers in a world that has ignored the voices of the affected. "When I am in a crowd, I search every face, hoping to find my father. I look at everyone, thinking maybe one of them is him. But I have never found him." Sitting at the Baluchistan protest camp, whenever she gets time, she writes letters to her father—letters that she has never been able to send. Her story represents the countless unheard voices of Baluchistan, waiting for justice and closure. "I always wonder, if my father were here today, how different my life would be. I wouldn’t be out on the streets like this. I wouldn’t have to protest."

Powered by Froala Editor